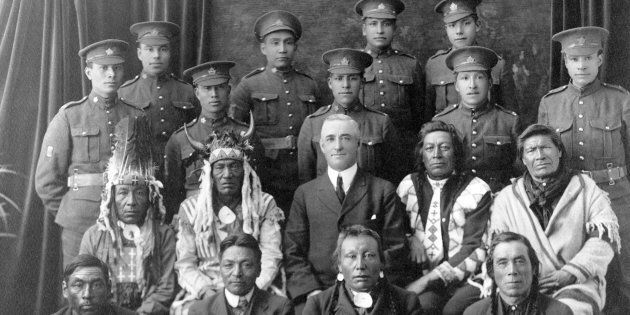

REMEMBRANCE DAY: Canada’s First Nations soldiers

“It’s a fact that, unlike non-aboriginal soldiers, First Nation soldiers were not recognized for their service until recently and received no pensions.”—Marlene Rice, elder-in-residence at VIU’s Cowichan campus.

We’re living in the age of Reconciliation. For the first time, many Canadians have turned the telescope around and are viewing their country and its history from the viewpoint of its Indigenous peoples.

It’s been a long, long road from the racism and segregation of colonialism to reach this point and we’ve a long way to go.

A good stepping-stone towards Reconciliation is the correction of a long overdue omission in our military heritage: honouring the contributions made by Indigenous servicemen in both world wars and Korea.

But we’re working on it. Four years ago, Citizen reporter Lexi Bainas wrote of a “never-before-seen” celebration at the Somena Longhouse on Allenby Road. This, explained spokesperson Marlene Rice, was the blessing of a totem pole carved by George Rice and a warrior canoe carved by Harold Joe, Roger and Cory George, Walter Thomas and George Rice in honour of First Nations veterans, not just from Cowichan Tribes, but also from afar.

The event opened at 8 a.m. that Remembrance Day “with a cultural ceremony first, blessing the totem pole and then the canoe that they have made.” This was followed by the Act of Remembrance at the Somena Longhouse. After lunch, there was a special remembrance of First Nations veterans, including the showing of photographs.

It was “the first time that First Nations veterans have ever been acknowledged,” she said.

“It was Harold Joe [who] got the idea from a Mainland ceremony,” and the local event saw the coming together of families, some from as far as the U.S., whose family members served in a war.

“We’re recognizing them for what they have done. It’s a great thing.”

The totem pole and warrior canoe were destined for permanent display at Vancouver Island University although the canoe can be borrowed by other First Nations who choose to use it in honouring their veterans.

According to government statistics, 12,000 aboriginal people along with an undetermined number of Inuit, Métis and non-status aboriginals served Canada in the First and Second World wars and the Korean War; 500 were killed and many more were wounded. That’s more than any other ethnic group in Canada as a percentage of their population. Since then, others have served and are serving in overseas peacekeeping missions.